Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Overview

- Dar es Salaam is the commercial capital of Tanzania, and has a population of some 4.0 million. It has chronic traffic congestion for long periods of the day, both into the city center and across the central business district.

- A range of bodies are responsible for planning and regulation of transport services in the city, but there is a lack of effective co-ordination.

- A Bus Rapid Transit system (DART) has been planned over the past decade, and construction contracts are now being let.

- Public transport is mostly provided by dala-dalas – private-sector minibuses – with very few large buses; these are supplemented by micro-transit that acts to increase traffic congestion.

- Public transport operations are not subsidized, but there is provision within the regulations to allow this for regular transport.

- Dala-dala tariffs are controlled, though both passengers and operators are dissatisfied; micro-transit fares are set by individual negotiation.

- Only the publicly-owned bus company (UDA) operates a ticketing system, though not all buses are equipped with ticket-issuing machines. Dala-dala passengers can demand a receipt, but these are informal documents.

- DART intends to introduce electronic smart-card ticketing for its services and those of its feeders, but the system specification is not yet developed.

Scope of the Case Study

This case study deals with the Fare Collection systems currently in use for urban transport in Dar es Salaam, and the plans for the forthcoming DART bus rapid transit system.

Background and City Overview

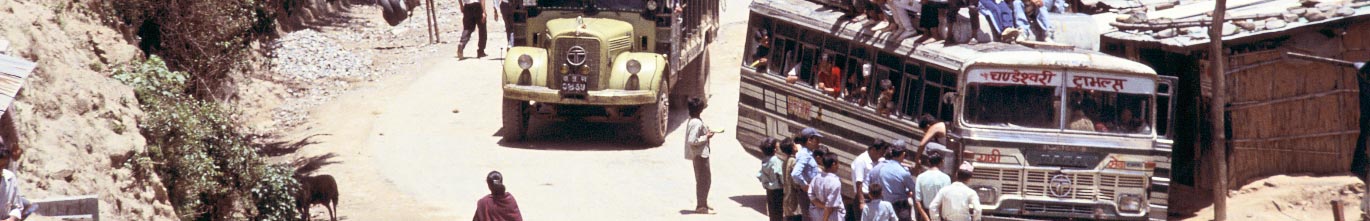

Tanzania’s urban population is growing rapidly at around 4% per year. The city of Dar es Salaam faces particularly difficult challenges in dealing with urban traffic growth. The central business district is highly constrained on two sides by the sea and a shipping channel. Urban densification is taking place across the city, both in the suburbs and the city centre with new high rise buildings.

At the same time insufficient attention has been given to public transport or to the adequate provision of new road space, connections and access. As a result ordinary journeys to work are difficult and problematic, with many people spending four (and more) hours each day on commuting

City Characteristics and Urban Growth

Dar es Salaam is the largest city and the commercial capital of Tanzania. The metropolitan area has an estimated population of approximately 4.0 million, compared with the national population of 30 million. By 2030 the population of Dar es Salaam is predicted to rise to 5.8 million (Dar es Salaam Transport Policy and System Development Master Plan, 2008) and possibly to 6.7 million (Dar es Salaam Rapid Transit Study).

Whilst the national legislative and government administration capital is located in Dodoma, Dar es Salaam remains the industrial, commercial and financial capital and also has the major specialist referral hospitals and the major academic-educational institutions. It is also contains the largest port, the key railheads and the main international airport of Tanzania.

Urban Management

The Prime Minister’s Office – Regional Administration and Local Government [PMO-RALG] is responsible for monitoring the standards of 132 local districts [municipalities] which are grouped into 26 Regions, each with a Regional Secretariat. The Dar es Salaam Region comprises of just three large urban municipalities: Ilala, Kinondoni and Temeke.

The municipalities are sub-divided into Divisions and Wards for local representation. Councilors from these three municipalities are also nominated to the Dar es Salaam City Council, which also includes the seven Members of Parliament for the City plus nominated special representatives for women.

Urban Planning Characteristics

The Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements [MLHHS] has responsibility for urban land planning, including urban planning in Dar es Salaam. It is responsible for ensuring that the agreed objectives embodied within the Master Plan and are protected to prevent infringements that could distort the plan. The 1979-1999 Master Plan is now being reviewed.

The planning process requires that planning applications are reviewed at Dar City Council and at local municipal levels and that any locally approved proposals are then sent to the Dar Regional Commissioner for comment by their professional staff.

It should be noted that:

- MLHHS does not issue standards and guidelines for detail planning proposals such as for bus stops and minor transport infrastructures.

- the location and concepts of major terminals and major taxi stations would need to be accommodated within any Master Plan review possesses.

- the formal linkage between urban planning and transport planning is not well evidenced

- the impact of major development schemes on both travel demand and upon vehicle parking requirements are also not well evidenced

Urban Mobility and Access Characteristics

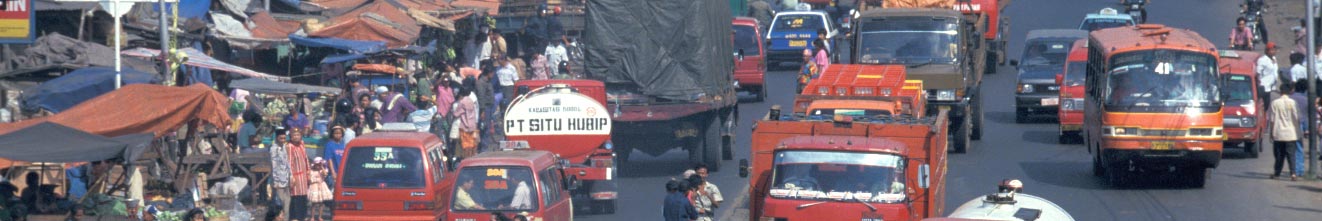

Dar es Salaam has chronic traffic congestion throughout long periods of the day on weekdays, especially along the main roads into the city centre and across the Central Business District [CBD]. Mobility is hampered by many vehicle movement conflicts, by the unpredictability of traffic signals, by restricted road widths created by vehicle parking indiscipline, and also by buses and taxis stopping anywhere and everywhere and without notice to collect and set down passengers.

There is a diverse and unwieldy array of public transport owners and operators with no organized structures. There is no sense of the cohesive and orderly planning and management of public transport supply and there appears to be no one organization responsible for transport supply or for travel information in the city.

Transport Financing

State revenues from public transport in Tanzania are varied, but can be summarized as:

- The Surface and Marine Transport Regulatory Authority [SUMATRA] collects fees for the issue of permits that authorize bus and dala-dala operators to operate specific vehicles on specific routes. This applies both nationally as well as elsewhere within Dar es Salaam. It also has authority to impose fines and penalties on operators who do not observe the conditions attached to the permit to operate.

- The Tanzania Revenue Authority [TRA], an Executive Agency under the supervision of the Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, has a wide range of powers and related responsibilities to collect all forms of revenues upon behalf of the government. It includes income tax from bus operators and driver and vehicle licensing revenues.

- The Roads Fund Board, which collects fuel taxes, is a major source of finance for the maintenance and repair of roads in Tanzania. It disburses funds to three implementing agencies

- Local Municipalities, who raise fees from taxi permitting and car parking fees and fines. Dar City Council also owns an inter-city bus terminal and is part owner of UDA, a small scale formal bus operator.

Public transport operations are currently not subsidized, directly or indirectly. Local Regulation 3-17 is stated to enable regular transport to be subsidized, but it is not exercised.

National Strategies – Transport

National Transport Policy

Guidance on urban and wider national transport policy is provided by the 2003 National Transport Policy [NTP].

However the NTP does not refer to later policy initiatives, major institutional reforms and current issues of concern or with the Government’s overall strategy for economic growth and poverty reduction, MKUKUTA I, the national strategy for growth and poverty reduction, and other initiatives such as the Tanzania Development Vision 2025.

The NTP was to ensure compliance to the national social and economic development objectives and goals, paying due emphasis to:

- support the short and long term development programs for sustainable economic growth, economic reforms, meeting basic needs, human resource development and creation of employment.

- ensure private sector participation in the provision of services while the government continues to retain the role of ownership and development of the key strategic transport infrastructure.

- apply a participatory approach in the provision of transport infrastructure and services by involving all the stakeholders (i.e. government, operators and users) in playing their roles in the development of the sector.

- provide effective institutional arrangements, laws and regulations, capacity building and use of appropriate technology.

- support appropriate development strategies including development corridors, land use densifications and efficiency and integrated economy through among others, establishing a strong infrastructure base and services in all major towns and other centers of socio-economic activities and growth.

- facilitate sustainable development by ensuring that all aspects of environment protection and management are given sufficient emphasis at the design and development stages of transport infrastructure and providing services.

National Development Plan

The next long-term National Development Plan is being prepared for the period up to 2025. This will also be a basis for the formulation of the next long term-term investment plan for the transport sector up to the year 2005. When completed, together with the reviewed transport policy, it can generate a comprehensive list of transport initiatives for Government.

National Development Vision 2025 and MKUKUTA II

A key influence on national policies is generated from the National Development Vision 2025 [NDV 2025], which is the main reference to national policy in Tanzania; the objective is “ to raise the standard of living of Tanzanians to a typical medium-level developed country by the year 2025”. The emphasis is hence on promoting economic growth.

This is reinforced by MKUKUTA II, which underpins the overall strategies in fulfilling NDV 2025. MKUKUTA II also promotes a series of strategies to benefit all Tanzanians, including:

- reducing income poverty through promoting inclusive, sustainable and employment-enhancing growth.

- ensuring creation of productive and decent employment, especially for women and youth.

- allocating and utilizing national resources equitably and efficiently for growth and poverty reduction, especially in rural areas.

- implementing comprehensive gender responsive and rights-based HIV & Aids programs for employees and their families, in both formal and informal, and public and private, sectors (Workplace Programs)

All Tanzanian government policies and programs must reflect NDV 2025 and MKUKUTA II.

Regulation and Competition

Regulation is complex with responsibilities spread between PMO-RALG and its various municipalities, with SUMATRA, the Executive Agency which is responsible for surface and marine transport regulation, and with the Tanzania Police Force and the Tanzania Revenue Authority. When operative, regulation would include some responsibilities currently held by DART.

The Ministry of Transport [as the recent successor to the Ministry of Infrastructure and Development] has responsibilities for some aspects of road transport regulation and it is the sponsoring Ministry with oversight of SUMATRA which provides, among other regulatory responsibilities, road transport regulation services.

Competition exists in the market, in that operators on the same route compete with each other for passengers as well as limited competition between dala-dalas and three-wheelers and also motorcycles for some short-distance trips outside of the CBD. [Smaller vehicles are prohibited from the CBD]. There is also very limited competition with hired taxis, as most public transport users cannot afford the high taxi fares.

At present there is no competition for the market, as there is free and unquantified entry into the sector, subject to possession of an authorized and insured vehicle and with a driver possessing a valid driving permit.

Transport Infrastructure

There are few dedicated public transport infrastructures in Dar es Salaam, except for an unquantified small number of bus shelters, occasionally with a lay-by. There are several dedicated long distance coach stations and also a former downtown longitudinal platform configuration bus station which is now used by taxis and also for car parking.

There are no bus priority schemes or dedicated bus lanes, although two key downtown boarding points [at ‘Posta’ and also at the Zanzibar Ferry Terminal] have extended bus stopping bays that accommodate the many minibus routes that terminate there. Dala-dalas in suburban areas congregate at roundabouts and intersections as few dedicated sites have been allocated for their use.

Bajaj operators and motorcycle operators each need separate parking areas from dala-dala vehicles. They tend to congregate in the vicinity of dala-dalas and also intrude upon taxi parks. The municipalities are in the process of identifying sites for these two new modes.

Urban Transport Institutions

The institutions with responsibilities for urban public transport are:

- PMO-RALG – monitoring of the activities of the municipal administrations

- PMO-RALG – supervision of DART BRT activities

- Ministry of Transport – compliance with national sectoral standards

- Ministry of Transport – supervision of SUMATRA activities

- Ministry of Finance – supervision of TRA activities

- Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements- monitoring of planning compliance

- Ministry of Home Affairs – supervision of Police activities

- Local Municipalities – supervision of taxi operations and taxi stations and some infrastructure provision responsibilities

- SUMATRA – issuance of operating permits to transport operators and monitoring compliance

- Tanzania Revenue Authority – taxation compliance in all areas of responsibility

- Tanzania Police Force – compliance with vehicle and driver examinations and activities

- DART – system manager for planned BRT system

- Service Providers – the bus, dala-dala, taxi, Bajaj and motorcycle transport operators

Transport Service Providers

The modes delivering public transport in Dar es Salaam are:

- formal ‘large bus’ transport – a small fleet of conventional standard size single-deck buses run by Shirika la Usafiri Dar es Salaam [UDA]

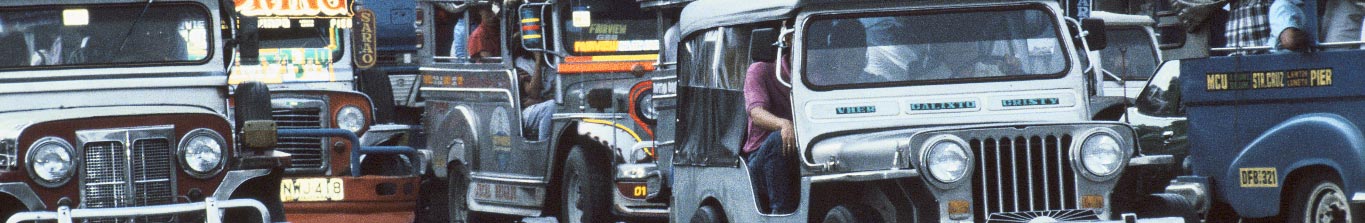

- dala-dala transport – mainly second-hand Toyota ‘Coaster’ and similar types of minibuses, plus in suburban areas, smaller Toyota Hi-Ace type and similar types of minibuses.

- three-wheeler auto-rickshaws, u commonly called ‘Bajaj’ vehicles.

- 2-wheeler public motorcycles

- roving saloon taxis, often parked at official and unofficial ranks.

Formal transport has a minimal presence on street whilst the dala-dala vehicles are ubiquitous and are the dominant and primary providers of public transport across the city. Bajaj three-wheelers and public motorcycles are relatively more expensive and are evident mainly at major suburban interchange sites: they are growing in numbers. Taxis are frequent and readily available but are considered expensive and used only by the more affluent.

Urban Transport Regulation

PMO-RALG monitors and advises upon the activities of the municipal administrations, including upon urban transport planning and traffic management generally.

Public Transport Regulation

Public transport regulation is complex with a range of responsibilities spread between five institutions.

The legal basis of acquiring operating permits for public transport in Tanzania is embodied in:

- The Transport Licensing [Road Passenger Vehicles] Regulations 2007 [supplement 38 to the Government Gazette, of 26-10-2007.

and more recently:

- The Transport Licensing [Motor Cycles and Tricycles] Regulations 2010 of the Government Gazette, of 02-04-2010

Both regulations follow a similar general format:

- Preliminary Provisions

- Applications for Road Service Licenses

- Issuance of Road Service Licenses

- Conditions of the Road Service License

- Authority to Issue Rod Service License

- Procedures, Suspension and Revocation of Road Service Licenses

- General Provisions

- Offences and Penalties

The regulations are each detailed and prescriptive and are proving challenging to implement and monitor, given the high volumes of vehicles involved and the limited regulatory staff and resources available.

Prime Minister’s Office – Regional Administrations and Local Government

The PMO-RALG is responsible for monitoring the standards of local municipalities which are then grouped into Regions, each with a Regional Secretariat. The Dar es Salaam Region comprises of just three large urban municipalities, Ilala, Kinondoni and Temeke. The municipalities are sub-divided into Divisions and Wards for local representation.

Dar City Council is responsible for bus stops and bus stations across Dar es Salaam - there are only 2 bus stations although more are alleged to be needed. There are few bus stops and buses often stop on the road which causes severe traffic congestion.

The PMO-RALG is also responsible for the oversight and supervision of DART activities

Ministry of Transport

Ministerial responsibilities concerning urban transport are gathered within the Surface Transport Section of the Transport Services Division of the Ministry. It is responsible to:

- initiate and formulate/review policies and strategies for development of road and rail transport services

- oversee and co-ordinate performance standards

- monitor and evaluate transport performance

- participate in restructuring/divestiture/privatization

- initiate regulatory & legal frameworks for surface transport

- oversee performance of the Executive Agency, SUMATRA

- compile and maintain sub-sector data bank

The emphasis is upon standards and policies rather than direct operational issues; although it does have formal oversight of SUMATRA which includes the regulation of road transport activities.

Surface and Marine Transport Regulatory Authority [SUMATRA]

This is the national multi-sector regulatory agency for transport [excepting air transport]. It is an Executive Agency under the supervision of the Ministry of Transport.

SUMATRA functions through four modal Directorates, one of which concerns road transport. There are also Directorates for Economic Regulation and for Corporate Affairs.

The Directorate for Road Transport Regulation is responsible for the road transport sub-sector with specific responsibilities for:

- registering and licensing commercial vehicles;

- determining and/or monitoring national and international yardsticks / benchmarks which can be sued in the determining the reasonableness of charges / rates / tariffs by the providers of road transport;

- formulating and reviewing codes for the providers and users if the road transport sector services, the ‘conditions of carriage’, attached to operating permits;

- in collaboration with other stakeholders, overseeing investigation in road traffic accidents;

- liaising with police, ministry of public safety and security and the ministry of infrastructure development on issues affecting road transport;

- developing the rules and regulations in road transport;

- reviewing, regulating and setting tariffs and charges;

- issuing permits to operate public transport vehicles over 7 seats [not taxis!];

- monitoring of activities to ensure compliance;

- undertaking studies, including travel demand studies on bus routes;

- supporting safe operations of public transport;

- supporting competition in the market [not monopolistic];

- addressing environmental impact of public transport [remissions].

The Directorate has two sections, one for Technical, Safety and Environmental Regulation, plus another for Licensing and Monitoring. It has branches in most main cities. In 2010 it was stated that SUMATRA had ‘not more than 20 persons’ engaged in local activities.

SUMATRA was responsible for monitoring activities and as an experiment, it had been sub-contracted to the private sector but was abandoned after complaints from operators.

The main infringements were:

- Overcharging of fares [even though fare rates were painted on vehicle sides];

- Drivers not in uniform;

- Illegal operators running without any Permit.

SUMATRA is split into 14 Zones, each with a small staff that undertakes the issuance of operating permits to local operators and liaises with other institutions on public transport matters.

Zone offices are also responsible for managing the primary collection and data analysis tasks related to changes in transport fares, although fares change decisions are made centrally at the SUMATRA headquarters, after having liaised with the associate body, the Consumer Affairs Council. The various Zone Offices also provide activity summaries monthly to SUMATRA headquarters. The zones are to be disbanded and replaced by regional offices in 25 regions.

The issuance of road service operating permits for vehicles is governed by the Transport Licensing [Road Passenger Vehicles] Regulations 2007 and also by the Transport Licensing [Motor Cycles and Tricycles] Regulations, 2010. To issue an operating license requires:

- a valid Vehicle Registration Receipt from the Tanzania Revenue Authority;

- a valid Police Vehicle Inspection Report.

Owners may request a specific route, although SUMATRA may require that an alternate route is selected if the requested route is considered already well supplied with buses. There were 126 different routes as at end 2009. Challenges existed in that:

- unlicensed buses appeared at peak periods or late evening on some routes;

- some buses operated on routes for which they were not authorized.

Each bus had a driver and a conductor. Working hours were regulated by the Labor Law of Ministry of Labor [max 12.00 hrs/day]

Note that SUMATRA allocates sufficient staff only for operator permit issuance - most enforcement responsibilities are with the Traffic Police [TPF]. SUMATRA appear to be only reactive to external requests for changes in public transport and are not pro-active in identifying needs and then planning accordingly. However, they do have a good database of permits issued and also provide a very useful liaison with operators that needs to be encouraged and formalized.

It is because of this staffing situation, that the monitoring of bus service delivery compliance is patchy and usually undertaken by the TPF with occasional more intensive checks with staff from SUMATRA, TPF and the municipalities working in together.

Note the unique situation of UDA, the small-scale formal bus operator in Dar es Salaam. It has a 25-year term operating franchise issued by SUMATRA to operate public transport in the city, with unrestricted route and vehicle volumes. In former times it had over 200 large buses, but competition from the small dala-dala buses had eroded patronage.

It should also be noted that the registration and permitting of public auto-tri-cycle and public motor cycles was only passed into law in 2010 and is in the process of being implemented in the urban municipalities. In addition, monitoring of their activities is also in progress – different municipalities appear to have progressed differently.

SUMATRA supported the greater participation of operator associations in developing local public transport. It is also responsible for the SUMATRA Consumer Consultative Council which was established within the SUMATRA Act, 2001.

Tanzania Police Force [TPF]

The Tanzania Police Force has responsibilities throughout the country for vehicle inspections and driver testing as a well as the monitoring and observance of the various road transport laws.

The TPF is arranged under the Inspector-General of Police with four Assistant Commissioners and also 24 Regional Command plus various specialist units. It has a Force Traffic Division [FTD] with responsibility for managing traffic activities. In Dar es Salaam, the FTD has Traffic Officers on duty at peak periods and at special events at major junctions and to control and improve the free flow of traffic.

Tanzania Revenue Authority [TRA]

The TRA collects transport sector revenues such as:

- sectoral employees income tax

- sectoral enterprises taxes

- sectoral-specific revenues, such as taxes and fees and fines on vehicles and drivers

It should be noted that:

- informal taxpayers [such as dala-dala or taxi drivers] are assessed and then banded for tax payment based on estimated annual income.

- dala-dala and taxi owners are interviewed and estimates made based on the size of the vehicle, the route to be used upon and sometimes an inspection of premises – usually they are placed on the highest informal tax band. TRA issued annual tax clearance stickers [to be placed in the vehicle windscreen] when payments are made.

- enforcement and monitoring is sub-contracted to an enforcement agency that stops and checks vehicles – where non-compliant, vehicles are impounded and only released after owners paid due and back payments, the fine for avoidance and the fees for impounding.

- owners with several vehicles are being instructed to migrate to the commercial business tax assessment process which then will mandatorily require their maintaining income and expenditure records with accounts audited by TRA recognized tax auditors.

- property tax is considered to be currently generating insufficient revenues. Temporarily TRA is collecting property tax as a proxy for the Dar local municipalities. Contracted professional specialists are undertaking the valuation of all properties in Dar es Salaam.

- during 2011, TRA expect to transfer the updated Dar property database and billings system back to the Dar local municipalities for them to administer and directly collect property taxes. The facility to change the rates of property taxation would be re-visited later.

Note however that if the volume of cash flowing through the transport sub-sector was forensically established, then the financial structure would be known and a justification may then be available for revising the legitimate tax revenue base. These revenues could be directly attributable to the sub-sector and a basis for hypothecating them to support the sector could be made.

Note also that, when operative, public transport regulation would include some responsibilities currently held by DART.

Short – Medium Term Plans

Analyses under review include:

- prioritizing the agreement with stakeholders for the local management of permitting processes for Bajaj and motorcycles to be used as public transport.

- the provision of separate off-street parking areas for Bajaj and motorcycles to wait for passengers.

- to restrict Bajaj and motorcycles operations to specific areas or suburbs, in order to contain and disperse activities to all areas of the cities. The operating restrictions would need to be incorporated into the permit issue conditions.

In addition, SUMATRA, after assessing transferring the responsibility for the issue of operator permits for Bajaj and motor cycles to the local municipalities, will then consider transferring similar responsibilities to the municipalities for the local dala-dala operating permits.

SUMATRA requires strengthening so that it:

- reviews the ways in which local decisions are made when assessing local public transport fares, to enable local municipalities to share ownership in the local decision-making processes.

- undertakes a review of the viability of operators in each of the public transport modes in order to establish typical costs and revenues and to devise sustainable business models.

Urban Public Transport Operations

Public transport is under-managed generally with users daily travelling in over-crowded elderly and demonstrably under-maintained vehicles. The business model of the operators seems unsustainable, as no new buses are purchased from funds generated by the sector. From a longer-term viewpoint, in order to discourage private motoring and to have better public transport, it is important that the bus operations are modernized.

Currently liaison between operators and the local institutions is informal. SUMATRA could develop more formal structures so that the operator Associations meet with the municipality, the Police and with SUMATRA on a regular basis so that the operators become part of the decision-making processes rather than recipients of regulation.

Ways in which a wider participation of the different types of vehicle owners and drivers within the membership of the Associations would also need to be addressed. In this way, management of change and migration to larger size buses could be discussed and new strategies could be developed. Confidence-building is a slow process and takes time to be achieved. It would also open dialogue with operators to identify practical measures to improve the convenience of public transport and to identify local parking and priority measures over other road users.

Buses

Shirika la Usafiri Dar es Salaam [UDA] is the sole remnant of formal city bus transport in Dar es Salaam. It is 51% owned by Dar es Salaam City Council and 49% by the Ministry of Finance with a nominated Board that meets quarterly. It has 20 large buses on 12 routes with 60 permanent staff and 50 contracted bus drivers on six-monthly contracts.

It employs 25 conductors and 10 revenue protection inspectors. SUMATRA authorized the same fares as those applicable for dala-dala transport. Contract trips and private hire trips are alleged to be profitable and cross-subsidies the public bus operations. UDA also operates 5 high-capacity dedicated school buses which are funded through a commercial bank funding initiative.

Dala-Dala Minibuses and Microbuses

It is estimated that there are over 6,000 dala-dalas operating officially in Dar es Salaam, although they may not account for the many owners who had left the sector and are no longer functioning.

There were three types of formal owner:

- The ‘sole’ business owner, who has no other economic activity.

- The ‘investor’ owner who each has +5 units [sometimes many buses] with contracted crews. Often family or friends helped in supervising daily activities. Investors often have other economic activities or work in government. This group is alleged to comprise about 40% of the total fleet in Dar es Salaam.

- Owner-operators with one vehicle, but who also have separate paid full-time employment [such as at a bank].

Individual owner-operators or those with 4 or less vehicles represented the balance 60% of all vehicles. Note that there are also a few [unquantified] illegal operators.

No verifiable data had been established on revenues, but the range of daily income per vehicle was stated to be between TShs 100,000+.

Operators complained about increases in the fuel price affected viability, the lack of bus stands [especially in the central areas], lack of protection from delinquent predator buses operating illegally on their routes, the poor highway conditions increased costs and slowed trips, and also that requests to increase fares were allegedly ignored or administered remotely in Dar es Salaam

Operational problems related to:

- drivers over speeding,

- drivers overloading with too many passengers,

- crew abusiveness to passengers, overcharging of fares,

- the refusal of drivers to reimburse fares when passengers are ejected short of the final destination

- drivers operating without a valid driving license.

The 7 to 11 seat microbuses that were previously operated in the City Centre had now been successfully and permanently relocated to providing suburban feeder bus operations.

Three-Wheeler Transport

Auto-rickshaws [Bajaj] vehicles are a newly emerging public transport mode and the processes of registration and permitting and the provision of facilities and regulation is still being developed yet increasing numbers of vehicles are to be seen.

The Bajaj vehicles are generally seen positively – cargo versions are sometimes replacing hand-carts which are useful – passenger versions work mainly in suburban and peri-urban areas.

Several challenges exist in relation to this form of transport. They include:

- difficulty in controlling on-street public transport activities [no SUMATRA staff available], reliance almost totally on traffic police to check the condition of vehicles and to check the behavior of drivers and their compliance with permit route conditions.

- fare changes had to be fully justified locally and consultation results and proposals sent to SUMATRA headquarters who would reach a decision and advise on decisions reached. Consultation with passengers, with operator associations, with schoolteachers, with the municipality, with the police and with others.

- driver education was needed and lack of professional driving skills was a problem.

Motorcycle Transport

Similar general comments also apply to Motorcycle transport. They are more numerous and are seen as more invasive, more dangerous to others and thus of more concern. Drivers are untrained, allegedly often unlicensed and generally unpredictable.

Local officials all expressed concern that the permitting processes needed to be resolved so that better enforcement could be made. In addition, ways to train and educate the drivers was considered important.

The DART Bus Rapid Transit System

PMO-RALG is responsible for high-level oversight of DART, the Executive Agency which is tasked with building and managing the Dar Rapid Transport network [a Bus Rapid Transit scheme using dedicated busways on main corridors]. At present DART remains in the initial phase with infrastructure works having been inaugurated in mid-2010 to build the busways, the terminals and garages to operate the system. The DART plans for a network of busways across the city in coming years.

Part of the remit is to contract with prior approved private sector bus operators to provide the bus services and also some feeder bus services, together with an associated smartcard ticketing system with an integrated revenues collection and distribution system. The various operational and technical criteria would be devised by DART and, to that extent, it would be a regulator of those contracted bus services.

Operating Conditions and External Characteristics

Dar es Salaam has chronic traffic congestion throughout long periods of the day on weekdays, especially along the main roads into the city centre and across the Central Business District [CBD]. Accessibility is hampered by:

- buses and taxis stopping anywhere and everywhere and without notice;

- many vehicle movement conflicts;

- restricted road widths created by vehicle parking indiscipline;

- unpredictability of traffic signals.

There is a diverse and unwieldy array of public transport owners and operators with no organized structures. There is no sense of the cohesive and orderly planning and management of public transport supply and no one organization is responsible for transport supply or for travel information in the city.

There is no coordinating mechanism that brings together the various institutions with transport responsibilities; without a common set of goals and strategies that enables transport planning and regulation to be undertaken in a cohesive and integrated manner, the current difficult conditions will remain.

Short – Medium Term Plans

DART activities will be an important feature of public transport in Dar es Salaam and they will need to be integrated within the wider planning and regulatory responsibilities for all forms of public transport.

Fare and Revenue Collection Characteristics

Dar es Salaam public transport is unsophisticated, including fares and revenues management. There are no on-vehicle or off-vehicle electronic ticketing systems in place on any mode at present and only the DART system plans to introduce such systems. UDA has a few elderly and outdated on-bus ticket issuing machines. There are no internet applications and all informal modes rely on a daily ‘hire’ charge payable to the vehicle owner with all surplus revenues retained by the crew. The concepts of revenue analysis or revenue sharing do not exist.

Ticketing Technologies

Revenue collection is almost universally cash-based single trip transactions and almost always informal – only UDA issues tickets and they represent less than 1% of all public transport trips. Other modes either never issue tickets or – in the case of dala-dalas – only issue an unnumbered receipt on request. It is rarely requested.

There are no plans for any mechanized or electronic ticket issuing systems except for the future DART operations which plans to adopt a smartcard system. It remains as a developing objective and is not close to finalization at present. Therefore, the consideration of IT systems and sophisticated revenue analysis systems is not otherwise under active consideration, although senior management in SUMATRA, PMO-RALG and DART [and to a lesser extent, the municipalities] are aware of future possibilities. This is not evident among informal operators or owners.

Note that there is a high level of acceptance and use of mobile phones [including bill payment schemes] across all population groups and there is a steady use of ATM cash machines by the employed. Therefore, the migration to modern smartcard ticketing systems is conceivable, although the sector lacks leadership and the vision to proceed, primarily because the organization of the sector is fragmented and under-resourced.

Tariff Affordability

There are fares conflicts between operators [who allege they are losing money] and passengers [who consider fares too high]. Transport costs have been estimated at between 7% and 18% of monthly expenditure for most regular dala-dala users, though, a ratio that is not excessive compared with the costs of bus transport operations in other developing countries.

Public funds are not available directly to subsidies urban public transport. SUMATRA is responsible for fares-setting but, whilst the change process is defined, the process of involving all stakeholders [that is passengers and operators as well as public authorities] justifies a review to enhance transparency, equity and to widen participation. Decisions are made centrally and on a national basis in Dar es Salaam, yet it would sensible to make local decisions that reflected the local characteristics of the different municipalities.

In most countries, public transport travel is funded by passengers paying fares for their trips and usually to the transport operator. The challenge is that the proportion of costs for the supply of transport varies – like most developing countries, in Tanzania, no public sector subsidy exists. As a result, most local operators allegedly make too little profit from their activities that they cannot replace their asset, the vehicle. When this happens, the quality of service delivery falls – the operators have in effect subsidized the travel, even if they have made a small cash profit on the day.

There is ongoing debate concerning public transport fares, with operators claiming the sector is no longer viable as costs have risen faster than fares, whilst passengers [mainly low-income groups] consider fares too high and unaffordable. It is quite valid that operators operate profitably, yet it is also equally valid that travel is affordable to the users

The Road Transport Directorate at SUMATRA focuses largely upon the issuance of operating permits through the close observance of a prescriptive and formulaic permitting process, yet the concept is absent of measuring demand or assessing user satisfaction and then in managing the development of the route networks. The fragmented vehicle ownership base and the casual and general acceptance of elderly vehicles and poor delivery standards contribute to a wide acceptance of the status quo. As a result, opportunities to migrate to better ticketing systems and to encourage a more professional approach to tariff setting is also absent.

Tariff Change Management

Fares are set or amended periodically when operator associations petition SUMATRA. The processes are:

- Operator Associations petition SUMATRA officially with detailed justifications.

- Submissions are discussed with the operator associations to understand the basis of change.

- SUMATRA develops a proposal with justifications.

- Proposals are sent to Consumers Consultative Council for their comments.

- On receipt of CCC response, SUMATRA Board considers comments and makes a decision.

- Parties can appeal to the Fair Competition Tribunal concerning the decision.

All informal transport modes are fragmented in ownership and are poorly organized in regards representation. Operator Associations have voluntary membership and many owner-operators do not participate. As a result, representation concerning requested changes in tariffs is undisciplined and is more representative of large-scale investors with small fleets of vehicles, rather than of individual owner-operators.

In addition, compelling and defendable data support that track increases in fuel and other major input costs are not seen. The carefully planned use of the media by Operator Associations to explain the need for tariff increases to the general public is not seen.

Modern tariff review systems would have a disciplined approach to how to review input costs that have changed both for the sector concerned as well as in wider national terms. In addition, the membership of the adjudicating committee would include locally based representation and well as taking formal note of views from passenger user and other groups. The formality of these concepts is not seen in Dar es Salaam.

The Consumers Consultative Council

Currently changes to public transport prices appear to be stimulated by operators who believe that they are not recouping sufficient income from their activities. It is valid that operators operate profitably, yet it is also equally valid that travel is affordable to the users.

The council operates under the supervision of SUMATRA, with functions including:

- representing the interests of Consumers by making submissions to, providing views and information to and consulting with the Authority, Minister and Sector Ministers;

- receiving and disseminating information and views on matters of interest to consumers of regulated goods and services;

- establishing regional and sector consumers committees and consult with them;

- consulting with industry; government and other consumer groups on matters of interests to consumers of regulated goods and services;

- establishing local and sector consumer committees and consult with them.

Tariff change proposals are referred to the CCC before being submitted for approval. The Council should consider widening stakeholder influence within the consultative process from among the sectoral communities. In particular influence from those groups that represent the passengers who use and pay for the road transport services that are provide.

There is low level of operating permit infringements. The Statutory Road Service License Conditions attached to the operator license shows 20 clauses that governs in some detail, all aspects of operation. Even a casual observer can see that the on-street delivery standards are quite different to those embodied in the permit conditions. This must be contrasted with the operating environment within which operators perform, so that strict monitoring of the conditions would quickly reduce the ability of the sector to meet the demand for transport.

Formal Transport

UDA adopts a distance-based fare structure employing on-board roving conductors [some female] to issue tickets. On some routes, conductors use electro-mechanical [Almex brand] ticket machines but the remaining conductors use ticket pads. Waybills are used to enter ticket sales details every trip. No weekly or monthly tickets are issued although the sales of monthly tickets are under review.

UDA is the only operator using ticket machines, although it did not foresee the early use of magnetic strip ticketing or smartcard applications. Revenues are collected on-bus – off-bus collections are occasionally undertaken at busy events, but this is very rare.

Current fare rates are:

- up to 2 kms – TShs 200 adult, 100 child

- up to 4 kms – TShs 300 adult, 100 child

- over 6 kms – TShs 400 adult, 100 child

Tickets are serially numbered and locally printed for pads – blank rolls are used for the for Almex machines.

The operator sets revenue targets per duty [the original targets were set after 4 days of close management observation of revenues taken]. Revenue excesses above targets are split between the conductor and UDA, whilst revenue shortfalls below targets – the conductor is penalized by 50% of shortfall value. UDA employs plain-clothes inspectors who observed activities and make personal phone calls to senior management to enable the culprit to be investigated immediately.

The existing ticket machines are maintained by a local company who orders spare parts as required from the foreign manufacturer. UDA has 2 Japanese Traincom M29 ticket machines under trial which ‘are more electronic’.

SUMATRA liaises with UDA on establishing operating costs, although the fares are allegedly too low and the operations thus run at a loss.

UDA is now a small-scale operator of large buses in a metropolitan city and it has no effective influence upon public transport supply or development. It aspires to attract significant investments from international transport groups or local investors to enable it to regain its former stature as a major provider of public transport in Dar es Salaam. In that context, investment in new vehicles and in modern ticketing technologies would be sought. The opportunity to achieve this through contracting with DART for the supply of feeder bus services is also an option.

UDA is in a parlous state and investment in modern ticketing systems will remain inappropriate unless it secures a successful change in business strategy that enables it to increase patronage and market share significantly so that there is then a justification in the investment in new ticketing equipment. Current arrangements do not show such planning being achieved.

Informal Transport Tariffs

Informal transport relates to dala-dalas, three-wheeler Bajaj vehicles and public motorcycles. Taxis are also considered. The fragmented operations and the individuality of owners is such that conventional business planning – or even operational planning – is primitive, based on common practice or non-existent.

The operational and financial characteristics of taxis of all types, of dala-dalas, auto-tri-cycles and public motorcycles are poorly documented and thus intelligent assessments of tariffs and ticketing systems have not been developed in a well informed manner. There has been no forensic assessment of passengers carried daily/weekly or of passenger classifications or of the financial models, including the dynamics between owners and operators

Dala-Dala Fares

Current fare bands within Dar es Salaam are for trips up to 5 kms, 5 to 10 kms and over 10 kms. Authorized dala-dala fares are based on distance and are painted on the sides of vehicles: they were, are TShs 150 / 250 / 350 but:

- Anecdotally, it was stated that significant revenues are generated by dala-dala daily operations and daily gross income generated of over TShs of 100,000 per operating vehicle was achievable.

- Fares are considered as too low [TShs 150-250-350, according to distance] to sustain and grow the sector. It is exacerbated by :

- the convention of allowing the military and police in uniform to ride without charge and without operator compensation. this is a cultural tradition with no legal basis.

- allowing students to travel at TShs 100 per trip [this is a traditional convention but revenue shortfalls are also not compensated to the operators]. Older children need to be in uniform and have proof of age identity with them at time of travel.

- cash is taken by the conductor on board, either at the time of boarding in peak periods but otherwise at any time, including when alighting, in quiet times.

- all conductors possess [un-numbered] tickets but usually these are only issued on request [rare] – non issue of tickets reduces the costs

- ticket issues are not often enforced [internally or by the Police] and minimal problems ensue.

- ticket touts at seen at many major stops [50~70% of stops?] – they operate illegally and often charge TShs 120 per stop/per large minibus or TShs 0.60 per stop per small minibus. They are illegal and uncontrolled.

- conductors sometimes ‘shout’ a fare on approaching stops at higher fares than that authorized and published on the bus sides.

- fares also rise illegally in wet weather [when demand suddenly rises] and when there is a low police presence on public holidays and in the late evenings.

Conductors are thought to earn TShs 5,000/day and drivers TShs 8,000/day – slightly above average income but there are long hours and a harsh working environment. [Many government staff earn TShs 100~150,000 monthly, but with several additional allowances].

The operational and financial dynamics of the dala-dalas remain largely unknown. A validated understanding of informal public transport is absent. Apart from the DART BRT system, opportunities to make improvements and of then migrating to more formal large-bus public transport remains just a broad aspiration, as tangible initiatives to plan and achieve sectoral change remain absent.

A defendable database of mode operating costs and revenues would provide an informed base from which tariff change issues could be considered more authoritatively and demonstrate equity in decision-making, both to operators and to users.

Bajaj and Motorcycle Fares

Motorcycles charged TShs 1000 per ride. Trips often run into the nearby hinterland unserved by dala-dalas and they do not conflict with them. However, they were considered as competition for taxis.

Bajaj operating permits owners were the responsibility of SUMATRA but passenger fares were not set. The permitting responsibilities were in the process of transfer to the Municipalities.

Neither modes issue tickets: ultimately, fares are subject to negotiation at the time of travel.

The Transport Licensing [Motor Cycles and Tricycles] Regulations, 2010 remain under recent implementation and require some retroactive registration of many vehicles that were already supplying public transport before the passage of the Regulations into law. However, the regulations are silent upon tariff setting. Fares appear to be negotiated with passengers at trip commencement.

DART BRT System

DART plans to use Smartcard ticketing technologies on their system, both on the BRT routes as well as on the associated feeder routes, although no system specifics had been finalized by early 2011 but it was ‘under consideration’.

DART plans to contract with several private sector bus operators to provide the bus services and also some feeder bus services. The smartcard ticketing system will be managed through a Revenue System Contractor. The objective is to create a common and integrated revenue collection and distribution system, with all participant operators.

There is no expressed synergy between the envisaged DART system components and the existing public transport systems.

Short – Medium Term Plans

Government are actively addressing the creation of an urban transport authority for Dar es Salaam and a pre-feasibility study had been competed in 2010. The study addressed, among other issues, the benefits of system-wide modern ticketing system which was applicable to most public transport modes. Assuming parliamentary approval of the concept, the legislative formation processes, formal establishment, funding, and then the inauguration of such an Authority are forecast to take several years. Ticketing is one of several key areas that an Authority could address once it was inaugurated.