Cost recovery from route operations

The proportion of costs recovered from fare-box revenues can be set at any level according to local political priorities and the resources available to fund the balance. International experience ranges from only a partial recovery of direct operating costs (typical in developed countries), full recovery of operating costs (with infrastructure and system management costs being met from central funds), through to full system cost recovery (including infrastructure maintenance) and a reasonable profit margin. Only the last is sustainable without external support.

Whatever the level of cost recovery that is determined for a service, its pricing needs to have a full understanding of the potential patronage and revenues, and of the costs incurred in meeting the quality-of-service standards that are set. Clearly that is a relatively easy task for an existing service that is operated by a formal regulated operator, especially one in public ownership, but is far more complex for any new service or one operated by the informal sector.

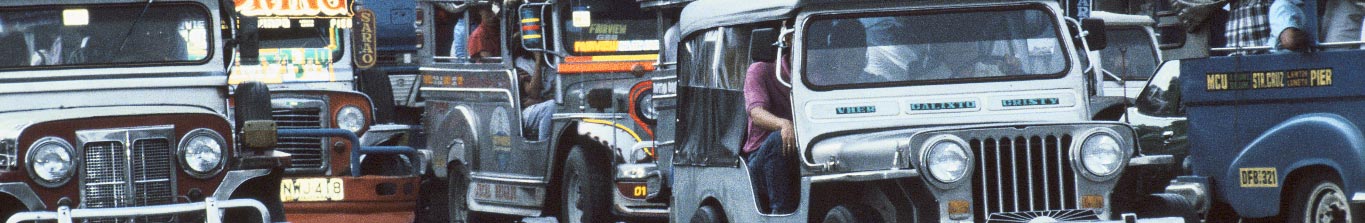

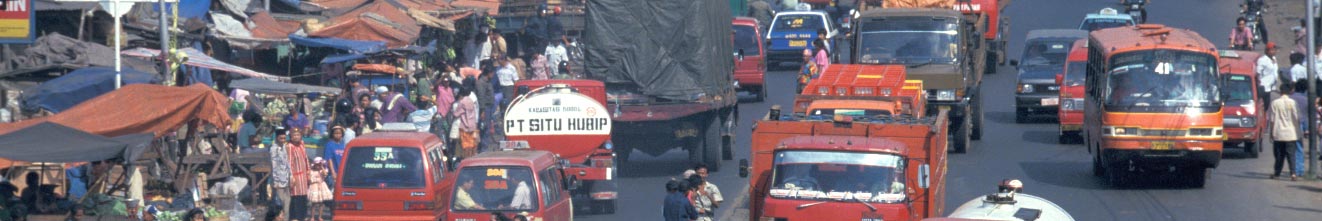

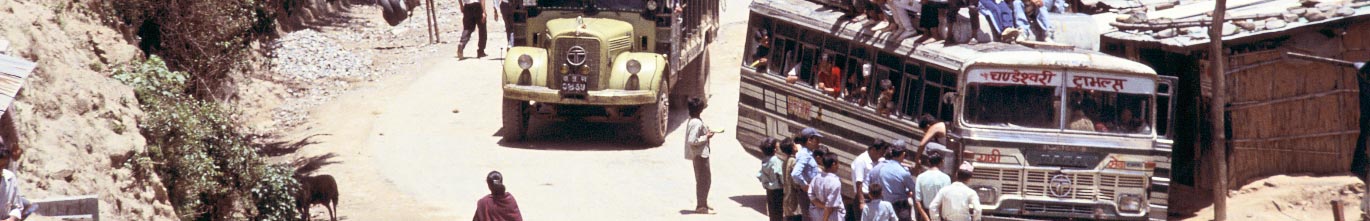

In order for planners to develop an accurate model for all the direct costs of operation of each applicable mode and vehicle size, they need to identify the factors driving those costs, and their respective unit costs and consumption rates (e.g. per kilometer run, or hour operated). Clearly there will be a wide range extending from the capital intensive modes that include new large-bus operations through to informal para-transit services that use old second-hand vehicles of little investment value. There will also be a variance according to the efficiency and practices of the service providers, and hence the costs that are being or reasonably could be attained.

Patronage can be estimated from personal travel surveys along the alignment of a new route, but these cannot identify ‘suppressed’ demand or accurately predict diversion from other routes when the new service is introduced. As such, a degree of judgment is required in forecasting, with a number of scenarios being developed for planning purposes. These will also identify the number of buses and kilometers of operation required at the set quality-of-service standard, and hence enable quantification of the costs involved.

A decision also needs to have been taken as to whether the level of cost recovery set by policy should apply to each individual service, or to the network as a whole. Should the former be applied, then passengers receiving the best service (in terms of speed and frequency) are likely to be paying the lowest fares, whereas peripheral residents (often the poorest) face higher rates. There is also the potential for confusion about applicable fares on common sections of route where different fares might apply according to the specific service.

If full cost recovery (commercial) fares are deemed socially inequitable, but a standardized fare rate is applied across the network, then mechanisms are needed to transfer funds from the financial surplus generated by high volume / low cost services to the operators of those that are less commercially viable through cross-subsidy. This may be achieved internally with a single network-wide operator, or with services tendered on a gross-cost basis by a transport authority that collects all revenues on a centralized basis.

To keep socially mandated (non-commercial) services secure under a net-cost contract regime with standardized fare rates, individual services would be tendered on the basis of either a minimum request for subsidy or a maximum premium bid for the operating rights, depending on their inherent viability. The transport authority would then be in a position to use the bid premiums to pay the subsidy requests, and achieve cross-subsidy in that manner. Alternatively, non-commercial services could be bundled with profitable ones in the bid packages, provided that there are operators of sufficient scale to operate the combined services.

Without such provisions, a free market will attract surplus supply to the most attractive routes (destroying their profit margins) and will result in little or no service in peripheral areas. Even with these provisions, mechanisms are still required to ensure that the full contracted operation of the non-commercial routes has actually been provided.

Almost by definition, private-sector services in an unregulated market are priced and provided so as to cover all their direct costs of operation (but not those external costs that they impose on society), and enable a return on the capital invested in the operation. Where government (or the authority) seeks to impose unrealistic fares control, this will either result in a reduction in service quality (e.g. shorter trips for the same fare, greater over-loading, or a reduction in hours of operation), in a reduction in investment (old vehicles, with little or no maintenance), or in a complete withdrawal of operators from part or all of the market.

However sub-economic fares / services can sometimes be imposed on a public-sector operator for political reasons, even though this is not sustainable in the longer term. If subsidies are then paid to cover their resultant losses, these distort the passenger transport market unless equal provision is made for any private operators (as is rarely the case). The consequences are similar to unrealistic fare controls, and are equally damaging to the network.